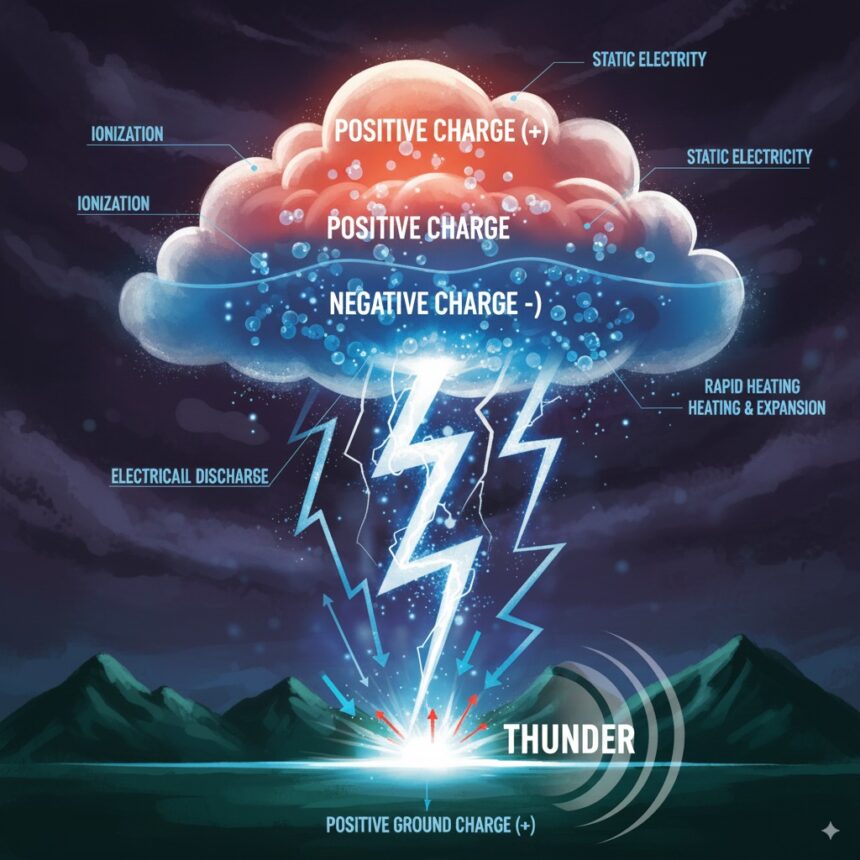

Lightning is a powerful natural electrical discharge that forms when large charge differences develop between parts of a cloud or between a cloud and the ground. Built up by collisions of water droplets and ice particles inside storm clouds, these charges can suddenly overcome the insulating effect of air and release a massive burst of energy that can strike the ground, another cloud, or the air itself.

Storm-cloud collisions of water droplets and ice produce electrostatic charge: positive near the cloud tops and negative near the bases, while the ground develops induced positive charge in response. Air normally acts as an insulator, but when the potential difference becomes large enough, the insulation breaks down and a discharge occurs. Before a cloud-to-ground strike reaches the surface, a stepped leader — a faint, branched, negatively charged ionized channel — propagates downward in small jumps. When the leader nears the ground, an upward connecting discharge from tall objects meets it, and a powerful return stroke travels back up the channel, producing the bright flash and the bulk of the energy transfer that we see as lightning.

Lightning occurs in several forms. Cloud-to-cloud lightning transfers charge between separate storm clouds and often appears as a bright flash across the sky. Cloud-to-air lightning discharges from a cloud into the surrounding atmosphere and can illuminate large areas without hitting the ground. Cloud-to-ground lightning is the most hazardous type; it sends current directly into the ground or into objects such as trees, poles, or buildings and can injure or kill people and animals nearby. Visual examples — a bright flash between two storm clouds, or a bolt striking a tree or a rooftop — can help readers picture these differences.

A single lightning strike can carry extremely high voltage and power. Typical lightning voltages can reach around 300 million volts, which is roughly 1.36 million times the voltage of a standard 220-volt household supply. That enormous energy can cause two burn points on a human body (entry and exit), cardiac arrest, severe damage to nerves and muscles, loss of consciousness, and in many cases death. If lightning hits a nearby object such as a tree or metal structure, the current can travel through the object into anyone touching it or standing nearby.

Because lightning can strike as far as about 10 miles (16 kilometers) from the center of a storm, safety precautions are important even when the sky overhead appears only partly cloudy. Safety recommendations from disaster management authorities include the following: avoid open areas during a thunderstorm and seek shelter inside a sturdy building or an enclosed vehicle with windows closed; do not shelter under trees or near poles and fences; avoid using umbrellas, metal objects, or holding mobile phones outdoors; and stay away from water activities such as swimming or boating, and avoid bathing or washing dishes at home during a storm because plumbing can conduct electricity. Remain indoors for at least 30 minutes after the last observed thunder.

Pay attention to warning signs that a strike could be imminent: if the time between lightning flash and thunder is short (less than about 30 seconds), the storm is close enough to be dangerous. Physical sensations such as a tingling on the skin or hair standing on end are immediate warnings; if that happens, lower your profile by sitting on the ground with your head between your knees and avoid touching the ground with more than the minimal contact required to sit. In an emergency, call for medical help immediately. Check the victim’s pulse and breathing; if breathing has stopped, start cardiopulmonary resuscitation while awaiting emergency services.

Clear, simple diagrams showing how charge separates in clouds, how a stepped leader and return stroke form, and where lightning can strike are especially helpful for public understanding. Given the extreme voltages involved and the potential for life-threatening injury, following basic sheltering and emergency-response steps can greatly reduce the risk of harm during thunderstorms.